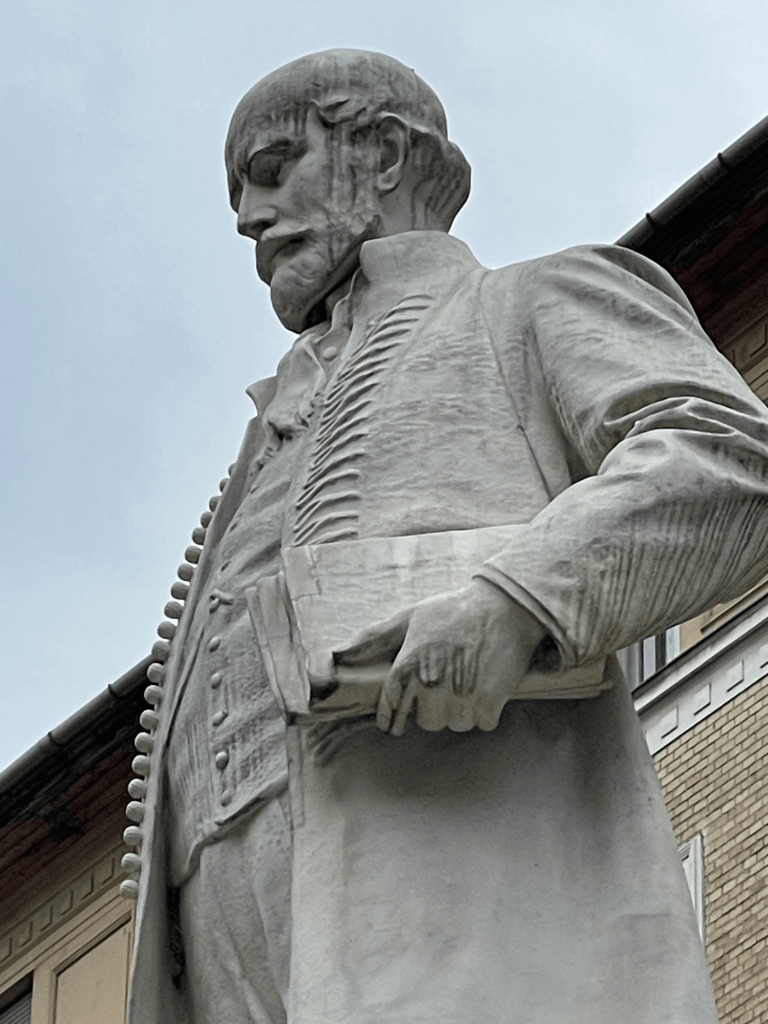

In March 2024 I was briefly in Budapest. I took the opportunity to make a pilgrimage to the famous statue of Ignaz Semmelweis. The Galileo of the 19th century, Semmelweis was a doctor who argued that washing one’s hands before delivering a baby would cut down on the incidence of mothers dying in childbirth. It did, dramatically and like magic, and it saved a huge number of women’s lives. That success irked his colleagues, however, and they had Semmelweis committed to a lunatic asylum. When he tried to escape the guards beat him to death.

Semmelweis was my age, 47, at the time. I went to see his statue with the following autobiographical passage in mind, written by Dr. Thomas Szasz in 2004 at the age of 84. I first read it 15 years ago and have never forgotten it:

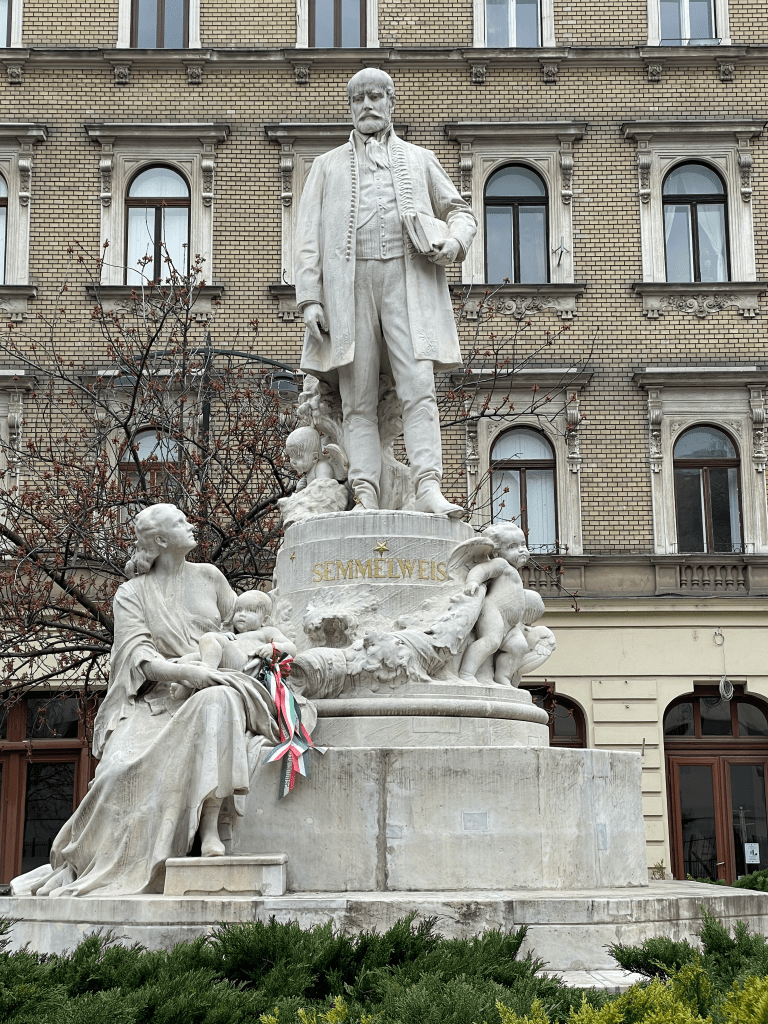

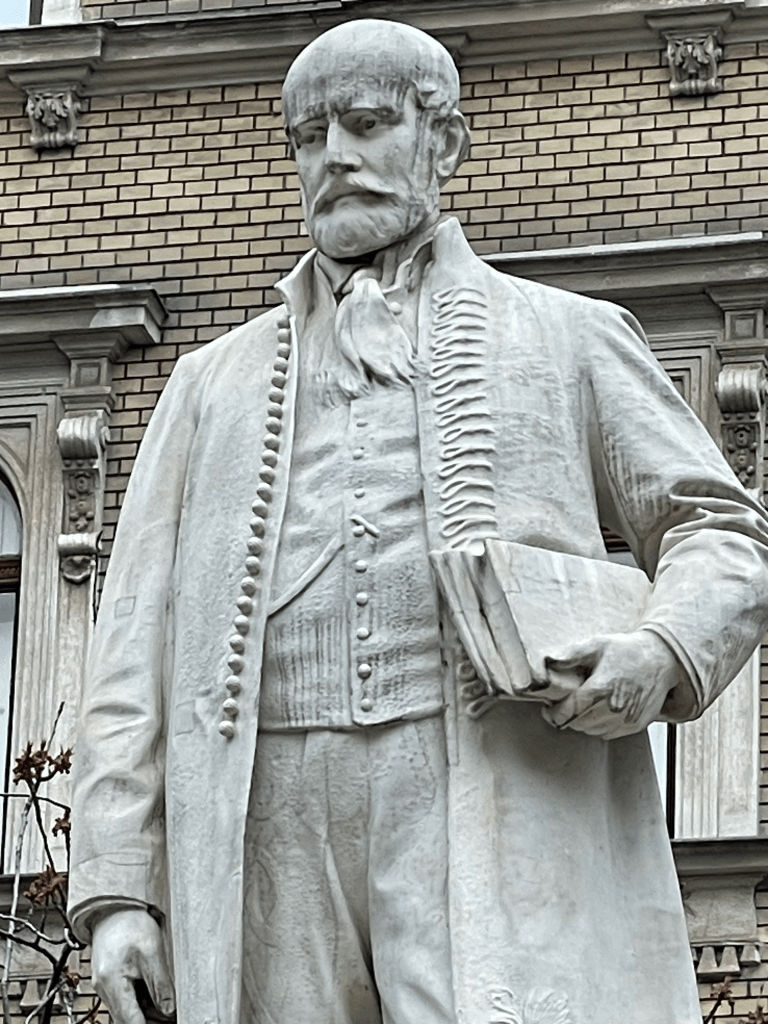

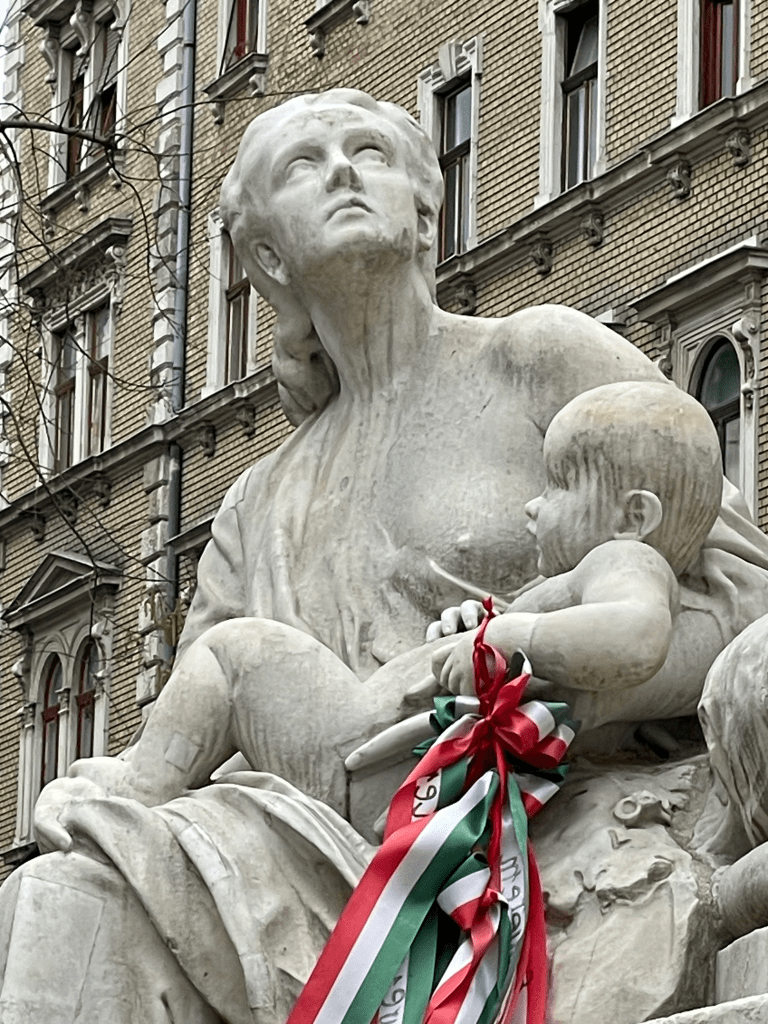

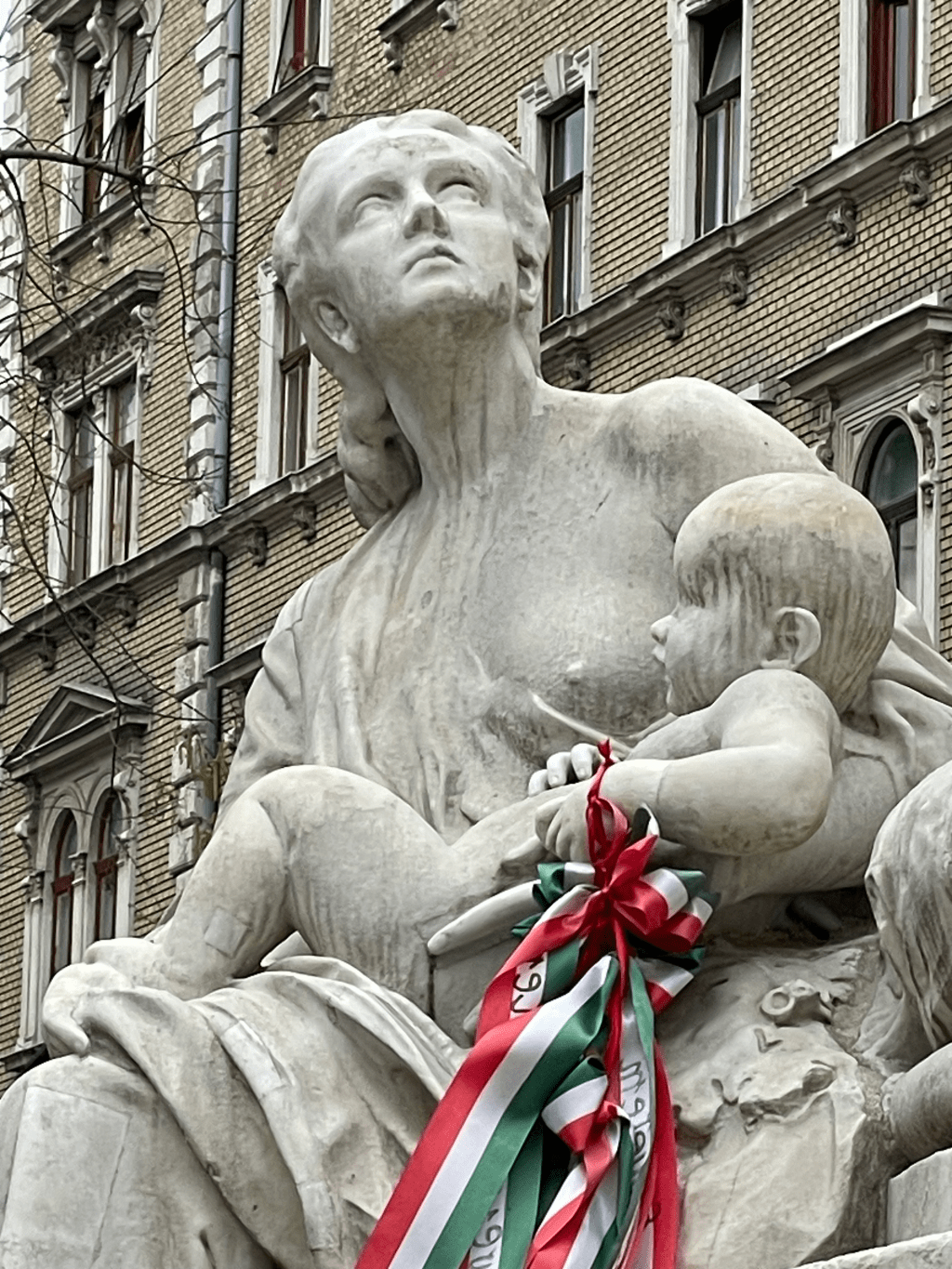

Before ending, however, I want to add a brief remark. During my years in the Gymnasium, I learned about the famous, nineteenth-century Hungarian obstetrician, Ignaz Semmelweis. I well remember Semmelweis’s statue situated in a small park in front of the St. Rochus Hospital, not far from the Minta Gymnasium. He is standing and, at his feet, a mother, cradling an infant, gazes up at him adoringly.

I was deeply moved by the story of Semmelweis’s tragic life. It taught me, at an early age, the lesson that it can be dangerous to be wrong, but, to be right, when society regards the majority’s falsehood as truth, could be fatal. This principle is especially true with respect to false truths that form an important part of an entire society’s belief system. ln the past, such basic false truths were religious in nature. In the modem world, they are political and medical in nature. The lesson of Semmelweis’s tragedy proved to be extremely helpful, virtually life-saving, for me. […]

A deep sense of the invincible social power of false truths enabled me to conceal my ideas from representatives of received psychiatric wisdom until such time that I was no longer under their educational or economic control and to conduct myself in such a way that would minimize the chances of being cast in the role of “enemy of the people” (Henrik Ibsen).

–Thomas Szasz, “An Autobiographical Sketch,” in Szasz Under Fire, p. 27-8

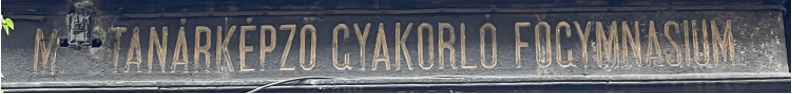

Here’s the former Minta Gynasium, now a university building. It’s a block and a half around the corner from the statue group. The guard only spoke Hungarian so I couldn’t get far inside, but I did peek in past him. There were a few plaques on the wall (in Hungarian) for famous alumni. None were for Szasz. I did see one for Edward Teller, though, which would not have been my own first choice…

And here is the famous statue group of Semmelweis, a mother, and her baby. It’s very moving to realize that this statue inspired Szasz himself and his life’s mission to reason man out of a mistake.

I took these pictures myself in March 2024. Feel free to share or reproduce them if you like — no credit needed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.